A Right for All: Freedom of Religion or Belief in ASEAN

The report documents ASEAN’s and the Member States’ approaches to the freedom of religion or belief, underscores the religious freedom-related challenges in the region that transcend country borders, and emphasizes the strategic importance of robust U.S. engagement on these issues with ASEAN as a collective and the 10 individual Member States.

The full report may be found here.

The ASEAN Report chapter translations may be found here.

Executive Summary

Overview

The countries of Southeast Asia—bound together in the regional bloc known as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)—are vastly diverse in their geographic size, governing systems, economies, and cultural and societal heterogeneity. Also, each country is different in its degree of adherence to international human rights standards and its protection (or denial) of the freedoms therein, including the universal freedom of religion or belief. In ASEAN’s 50th year, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) presents A Right for All: Freedom of Religion or Belief in ASEAN. The report documents ASEAN’s and the Member States’ approaches to this fundamental right, underscores the religious freedom-related challenges in the region that transcend country borders, and emphasizes the strategic importance of robust U.S. engagement on these issues with ASEAN as a collective and the 10 individual Member States: Brunei, Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

ASEAN’s approach to human rights often has been diminished by two competing interests: the Member States’ desire to integrate as a bloc and their deeply embedded reliance on independence and non-interference in one another’s affairs. In an increasingly interdependent, interconnected community such as ASEAN, it is vital that governments and societies recognize—both within and across their borders—when the right to freedom of religion or belief is being abused and take steps to protect individuals and groups whose rights are violated.

The United States—now in its 40th year engaging with ASEAN—wields significant weight and influence in the region and with individual Member States. The United States must encourage ASEAN Member States to achieve prosperity for their own people and live up to the core principles all countries agree to when joining the United Nations and upon becoming party to international human rights instruments.

ASEAN, Human Rights, and Freedom of Religion or Belief

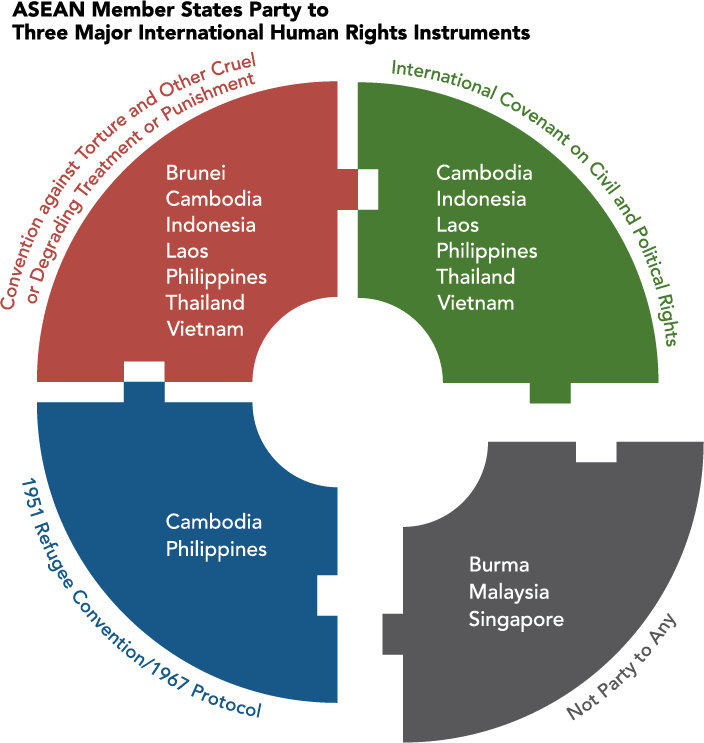

ASEAN and the individual Member States have an inconsistent record protecting and promoting human rights, and even more so with respect to freedom of religion or belief. Often, ASEAN countries have lacked cohesion and a strong will to act in response to serious violations within their own borders and among the other members of the bloc. In 2009, ASEAN established the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR), and in 2012 it adopted the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (AHRD). Critics have challenged the efficacy of the AICHR as a human rights body and the AHRD as a human rights instrument. The international community should call upon Member States to uphold the higher standards embodied in international human rights instruments such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

ASEAN and the individual Member States have an inconsistent record protecting and promoting human rights, and even more so with respect to freedom of religion or belief. Often, ASEAN countries have lacked cohesion and a strong will to act in response to serious violations within their own borders and among the other members of the bloc. In 2009, ASEAN established the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR), and in 2012 it adopted the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (AHRD). Critics have challenged the efficacy of the AICHR as a human rights body and the AHRD as a human rights instrument. The international community should call upon Member States to uphold the higher standards embodied in international human rights instruments such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

Key findings about freedom of religion or belief in the 10 Member States include:

Brunei: The identification of the state and the public sphere with Islam in the person of the sultan sometimes challenges the religious freedom of non-Muslims or heterodox Muslim residents, whose communities may be banned or ruled by Shari’ah despite their affiliation.

Burma: While the year 2016 marked a historic and peaceful transition of government in Burma, outright impunity for abuses committed by the military and some non-state actors and the depth of the humanitarian crisis for displaced persons continue to drive the ill treatment of religious and ethnic groups.

Cambodia: Cambodia has few internal challenges with freedom of religion or belief, but could do more to uphold its human rights commitments, particularly under the Refugee Convention.

Indonesia: The Indonesian government often intervenes when religious freedom abuses arise, particularly if they involve violence. Non-Muslims and non-Sunni Muslims, however, endure ongoing difficulties obtaining official permission to build houses of worship, experience vandalism at houses of worship, and are subject to discrimination as well as sometimes violent protests that interfere with their ability to practice their faith.

Laos: In some areas of Laos, local authorities harass and discriminate against religious and ethnic minorities, and pervasive government control and onerous regulations impede freedom of religion or belief.

Malaysia: Malaysia’s entrenched system of government advantages the ruling party and the Sunni Muslim Malay majority at the expense of religious and ethnic minorities, often through government-directed crackdowns on religious activity, expression, or dissent.

Philippines: With the strong influence of the Catholic Church, as well as the needs of other religious groups, the Philippines grapples with the separation of church and state, and also with the violence that continues to dominate relations with Muslims on the island of Mindanao.

Singapore: Singapore’s history of intercommunal violence informs its current policies, which prioritize harmony between the country’s major religions, sometimes at a cost to freedom of expression and the rights of smaller religious communities.

Thailand: The primacy of Buddhism is most problematic to freedom of religion or belief in the largely Malay Muslim southern provinces, where ongoing Buddhist-Muslim tensions contribute to a growing sense of nationwide religious-based nationalism.

Vietnam: Vietnam has made progress to improve religious freedom conditions, but severe violations continue, especially against ethnic minority communities in rural areas of some provinces.

Challenges

The 10 Member States experience a number of common and crosscutting challenges that underscore how violations of freedom of religion or belief occur across borders and within the context of broader and related regional trends. ASEAN should acknowledge and work to address the following problems: protection gaps for refugees, asylum seekers, trafficked persons, and those internally displaced; the use of anti-extremism and antiterrorism laws as a means to limit religious communities’ legitimate activities, stifle peaceful dissent, and imprison people; the use of nationalistic sentiment by individuals and groups who manipulate religion to the detriment of other religious and ethnic groups; arrests, detentions, and imprisonments based on religious belief, practice, or activities; and the existence and implementation of blasphemy laws that are used to incite or inspire violence, generally by members of a majority religious group against those from a religious minority community.

ASEAN’s Principle of Non-Interference

ASEAN Member States regularly invoke the principle of non-interference (the enshrined tenet of national sovereignty, integrity, and independence), but on occasion have set it aside when it was to their advantage. While the ASEAN countries understandably first and foremost protect their own interests, each has a broader responsibility to act in harmony with the community of nations, particularly when human rights issues, including freedom of religion or belief, transcend country borders.

U.S.-ASEAN Relations

During ASEAN’s 50th year and after 40 years of U.S.-ASEAN engagement, the United States should leverage its interest and influence in the region to press Member States to uphold international human rights standards. Although some of the ASEAN Member States are more open to U.S. engagement about human rights issues, strong and consistent prodding from the United States—including positive reinforcement when warranted—would send a clear signal about U.S. priorities in the region.

Conclusion

ASEAN and the individual Member States must understand that the global community of nations is grounded in the premise that everyone observe a rules-based international order, which includes the responsibility to uphold freedom of religion or belief and related human rights. This means ASEAN and the Member States should take steps to:

adhere to international human rights instruments; welcome visits by international human rights monitors; ensure unfettered access by aid workers, independent media, and other international stakeholders to vulnerable populations and conflict areas; repeal blasphemy and related laws; release prisoners of conscience; and strengthen interfaith relationships.

ASEAN Report Executive Summary and Chapter Translations

Brunei (Malay)

Burma (Burmese)

Cambodia (Khmer)

Indonesia (Indonesian)

Laos (Lao)

Malaysia (Malay)

Philippines (Tagalog)

Singapore (Malay)

Singapore (Chinese)

Thailand (Thai)

Vietnam (Vietnamese)